Indian Art in the Ashmolean Museum

A catalogue of the Ashmolean’s collection of Indian art by J. C. Harle and Andrew Topsfield (published Oxford, 1987).

Publications online: 143 objects

- Reference URL

Actions

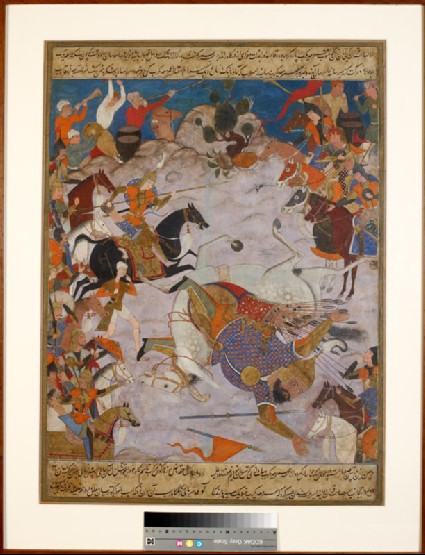

Amir Hamza defeats 'Umar-i Ma'di Karab

-

Literature notes

Akbar, the third and greatest of the Mughal emperors (r.1556-1605), was a ruler of unusual vision and restless energy. Inheriting the throne at the age of fourteen, he extended Mughal power throughout northern India, whilst taking a keen and tolerant interest in the religion and customs of his subject peoples. As a patron, he brought together a large atelier of native artists, many of them Hindus, under the direction of the Persian masters, Mīr Sayyid ‘Alī and Abd us-Samad, whom his father Humayūn had earlier brought back to India from his exile at the Persian court. Under Akbar’s close supervision a dynamic style of manuscript illustration was formed, combining Persian elegance of line and decoration with the robuster vitality of Indian painting and further naturalistic elements deriving from European art which had begun to reach the Mughal court. The main forcing-ground for this rapid stylistic synthesis was the illustrated series of the Dastān-ī Amīr Hamza (or Hamza-nāma), a rambling epic narrative, describing the fantastic adventures of its hero Hamza, which appealed greatly to the young Akbar. A chronicler tells us that on one occasion in 1564 (about the time that the Ashmolean page may have been illustrated) he amused himself after an elephant hunt by listening to its stories; and a later historian relates that he would even recite them himself to his harem in the manner of a traditional story teller.

The illustrated series originally comprised 1400 large paintings on cotton cloth, bound in fourteen volumes. This uniquely ambitious project occupied the imperial studio for about fifteen years (c.1562-77). The earliest illustrations, such as the present one, were produced under Mīr Sayyid ‘Alī’s direction and are often noticeably Persian in feeling. In many cases they also have the (paper) text panels on the painted side rather than the reverse, as became usual later. The subject here is an early episode in the epic, in which the youthful hero Hamza, encountering the gigantic warrior ‘Amr-i Ma’dī Kariba on the battlefield, topples both horse and rider with a mere thrust of his foot (subsequently ‘Amr-i Ma’dī is converted to Islam and becomes one of the Hamza’s staunch helpers). Instead of the explicit carnage seen in some of the later pictures of the series, this scene of combat has an element of comic bathos. While the corpulent warrior sprawls headlong, arrows spilling from his quiver, many of the onlookers ‘bite the finger of astonishment’ in the Perisan manner. The setting of the composition against a high rocky skyline with a stylized tree also adheres closely to the Persian pictorial tradition, though the spirited figures of trumpeters and percussionists above the horizon are more typically Indian.

At some point after the mid-18th century the 1400 pages of the Dāstān-i-Amīr Hamza were dispersed from the imperial library, and rather more than a tenth of them are now known to survive. Another page, showing Hamza burning the wooden chest of the Zoroaster (Glück) has recently been place on loan to the Museum. -

Details

- Associated place

-

Asia › India › north India (place of creation)

- Date

-

1562 - 1565

Mughal Period (1526 - 1858)

- Associated people

-

Akbar (ruled 1556 - 1605) (commissioner)

- Material and technique

- gouache on cotton cloth; black ink on paper

- Dimensions

-

frame 86.4 x 67.2 x 3 cm (height x width x depth)

painting 69 x 51 cm sight size (height x width)

- Material index

- Technique index

- Object type index

- No. of items

- 1

- Credit line

- Gift of Gerald Reitlinger, 1978.

- Accession no.

- EA1978.2596

-

Further reading

Harle, J. C., and Andrew Topsfield, Indian Art in the Ashmolean Museum (Oxford: Ashmolean Museum, 1987), no. 82 on pp. 75-76, p. xiv, pl. 13 (colour) & p. 75

Topsfield, Andrew, Indian Paintings from Oxford Collections, Ashmolean Handbooks (Oxford: Ashmolean Museum in association with the Bodleian Library, 1994), no. 1 on p. 8, p. 5 & p. 66, illus. p. 9

Gluck, H., Die Indischen Miniaturen des Hæmzæ-Romanes im Österreichischen Museum für Kunst und Industrie in Wien und in Anderen Sammlungen (Zürich: Amalthea-Verlag, 1925), 28, fig.2

Piper, David, and Christopher White, Treasures of the Ashmolean Museum: An Illustrated Souvenir of the Collections, revised edn (Oxford: Ashmolean Museum, 1995), no. 43 on p. 47, illus. p. 46 fig. 43

Location

-

- currently in research collection

Objects are sometimes moved to a different location. Our object location data is usually updated on a monthly basis. Contact the Jameel Study Centre if you are planning to visit the museum to see a particular object on display, or would like to arrange an appointment to see an object in our reserve collections.

Publications online

-

Indian Art in the Ashmolean Museum

Akbar, the third and greatest of the Mughal emperors (r.1556-1605), was a ruler of unusual vision and restless energy. Inheriting the throne at the age of fourteen, he extended Mughal power throughout northern India, whilst taking a keen and tolerant interest in the religion and customs of his subject peoples. As a patron, he brought together a large atelier of native artists, many of them Hindus, under the direction of the Persian masters, Mīr Sayyid ‘Alī and Abd us-Samad, whom his father Humayūn had earlier brought back to India from his exile at the Persian court. Under Akbar’s close supervision a dynamic style of manuscript illustration was formed, combining Persian elegance of line and decoration with the robuster vitality of Indian painting and further naturalistic elements deriving from European art which had begun to reach the Mughal court. The main forcing-ground for this rapid stylistic synthesis was the illustrated series of the Dastān-ī Amīr Hamza (or Hamza-nāma), a rambling epic narrative, describing the fantastic adventures of its hero Hamza, which appealed greatly to the young Akbar. A chronicler tells us that on one occasion in 1564 (about the time that the Ashmolean page may have been illustrated) he amused himself after an elephant hunt by listening to its stories; and a later historian relates that he would even recite them himself to his harem in the manner of a traditional story teller.

The illustrated series originally comprised 1400 large paintings on cotton cloth, bound in fourteen volumes. This uniquely ambitious project occupied the imperial studio for about fifteen years (c.1562-77). The earliest illustrations, such as the present one, were produced under Mīr Sayyid ‘Alī’s direction and are often noticeably Persian in feeling. In many cases they also have the (paper) text panels on the painted side rather than the reverse, as became usual later. The subject here is an early episode in the epic, in which the youthful hero Hamza, encountering the gigantic warrior ‘Amr-i Ma’dī Kariba on the battlefield, topples both horse and rider with a mere thrust of his foot (subsequently ‘Amr-i Ma’dī is converted to Islam and becomes one of the Hamza’s staunch helpers). Instead of the explicit carnage seen in some of the later pictures of the series, this scene of combat has an element of comic bathos. While the corpulent warrior sprawls headlong, arrows spilling from his quiver, many of the onlookers ‘bite the finger of astonishment’ in the Perisan manner. The setting of the composition against a high rocky skyline with a stylized tree also adheres closely to the Persian pictorial tradition, though the spirited figures of trumpeters and percussionists above the horizon are more typically Indian.

At some point after the mid-18th century the 1400 pages of the Dāstān-i-Amīr Hamza were dispersed from the imperial library, and rather more than a tenth of them are now known to survive. Another page, showing Hamza burning the wooden chest of the Zoroaster (Glück) has recently been place on loan to the Museum.

Notice

Object information may not accurately reflect the actual contents of the original publication, since our online objects contain current information held in our collections database. Click on 'buy this publication' to purchase printed versions of our online publications, where available, or contact the Jameel Study Centre to arrange access to books on our collections that are now out of print.

© 2013 University of Oxford - Ashmolean Museum